Childhood

Luis grew up in one of Santiago’s old neighborhoods. His father was a carpenter who had a small shop that grew bigger as Luis grew older. Eventually, it turned into a full-size furniture factory that made wooden furniture for radios (standard in the 1950s). When plastic came onto the market, his father’s business collapsed. “Plastic changed everything.”

Luis went to the University of Chile to become an agricultural technician. He ended up staying in Santiago for five years working in and studying Fruticulture (Pomology) – the improvement of fruit growing.

Luis grew up Catholic, and as he got older, he started moving up in the church and even planned on becoming a priest.

“I was called by God. I almost entered the seminary to be a priest, but I fell in love with the woman who was going to be my wife. Wife or be a priest? I decided, wife.” (audio below)

United States

Luis wanted to further his studies, but this time in the Humanities. The only problem was that in 1973 when Luis was a student, the dictator Augusto Pinochet came to power. Pinochet thought that anyone studying the Humanities was against him, so the University of Chile made all Humanities students, like Luis, switch to History.

Luis’s brother-in-law, a Chilean tennis champion, went on scholarship to Mississippi State. He returned to Chile with a degree in accounting and married Luis’s sister. She was the first to move to the US, then Luis’s parents moved too. Luis’ first time to Missississipi was to visit his sister in 1974.

“Mississippi was unknown to me. I was living with the judgment that Mississippi equals slavery, prejudice, and a lot of bad things. I was scared at first.”

To Luis’s surprise that first visit to Mississippi was a positive experience. In 1983, Luis did not like the way Chile was going politically or economically and applied for a visa to join his sister in the US.

Poultry Company

In 1990, after seven years of waiting, Luis was the last member of his family to arrive in the US. Luis, his wife, their three daughters (and little doggy) moved to Mississippi.

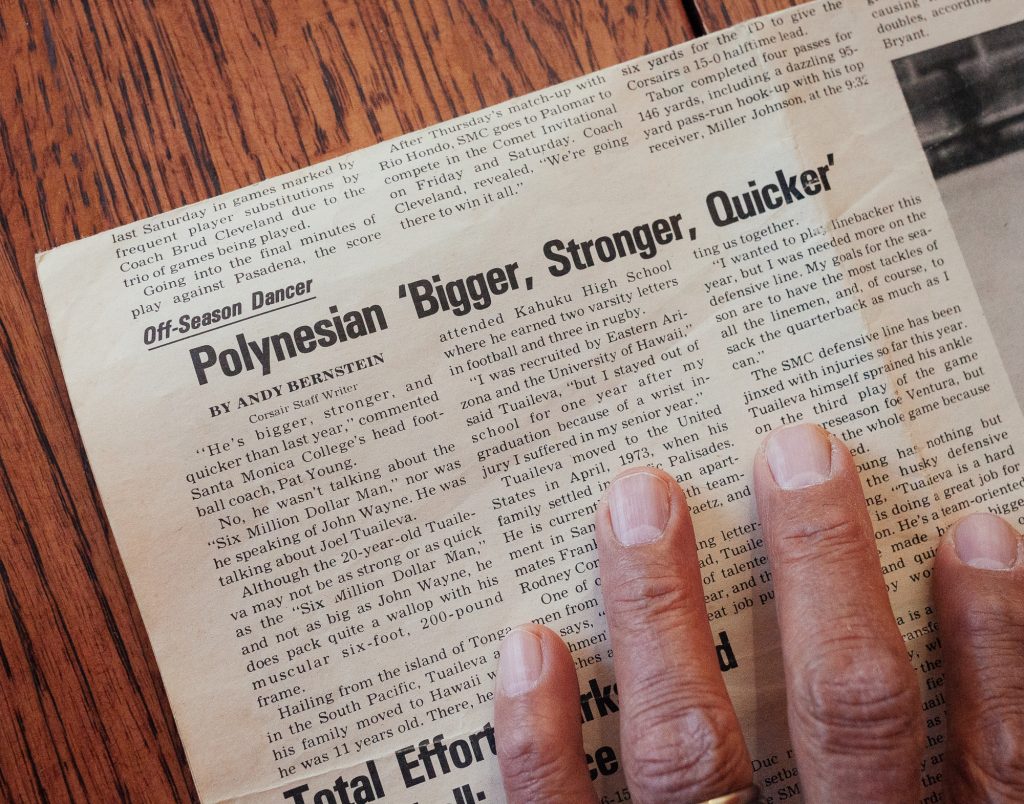

His brother-in-law, the former tennis champion, was now the vice president at a poultry company. That’s where Luis started working in Mississippi – on the plant’s floor. The company needed workers, as the local population usually didn’t want those jobs. If they did work at the plant, they would only work a few months, then quit. The company needed people who would stay and work – and knew immigrants would do that.

Soon Luis stopped working on the plant floor and became the coordinator for a new project, tasked with getting 300 new workers for the plant in less than a year. The company trained Luis on identifying proper documentation, and he would regularly go to Texas’s border to recruit. One major problem was they didn’t have anywhere for workers to live, and Luis had to find Morton’s empty houses to rent out for them. Luis worked on the project for more than a decade. He had hired almost five thousand workers by the time the poultry company was bought out by a massive conglomerate. When this happened, they laid-off Luis.

Luis, however, fondly looks back on this experience and feels like he helped many people.

“I am well known by the old people here. There are still families from that time that are here in the area. I came to this country as a worker, and I finished in a company here as a manager!”

Educator

After being laid off, Luis tried selling cars but didn’t like it, so he applied to be a janitor at the local school. He smiles, “They discovered that this janitor was educated!”

The school’s administration encouraged Luis to become an English Language Learner (ELL) teacher, and he has been teaching now for more than a decade. He is the only bilingual teacher and currently teaches at three different schools in the district. Luis loves helping the area’s growing body of Hispanic students. (audio below)

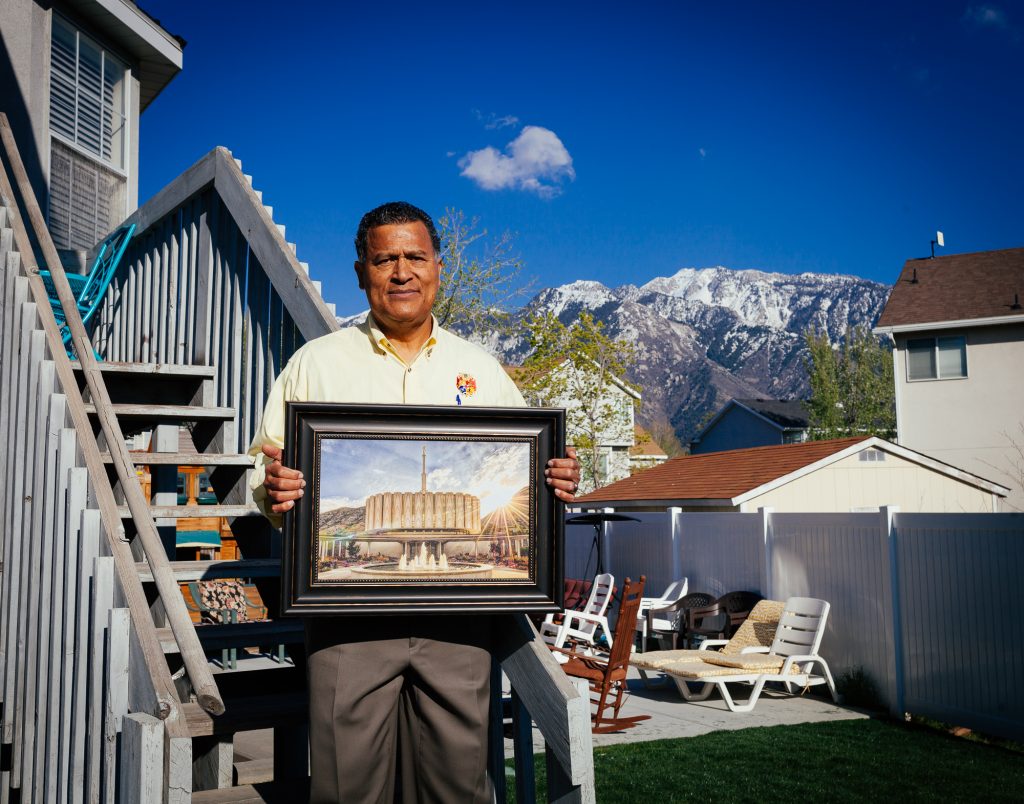

Church

After living in Morton for a while, he became involved in the local Catholic Church and eventually became a minister. He also started writing Christian columns in the local newspaper, something he has been doing for almost two decades. The more Luis learned about the Bible, the more he started to question some of the things the Catholic Church was teaching.

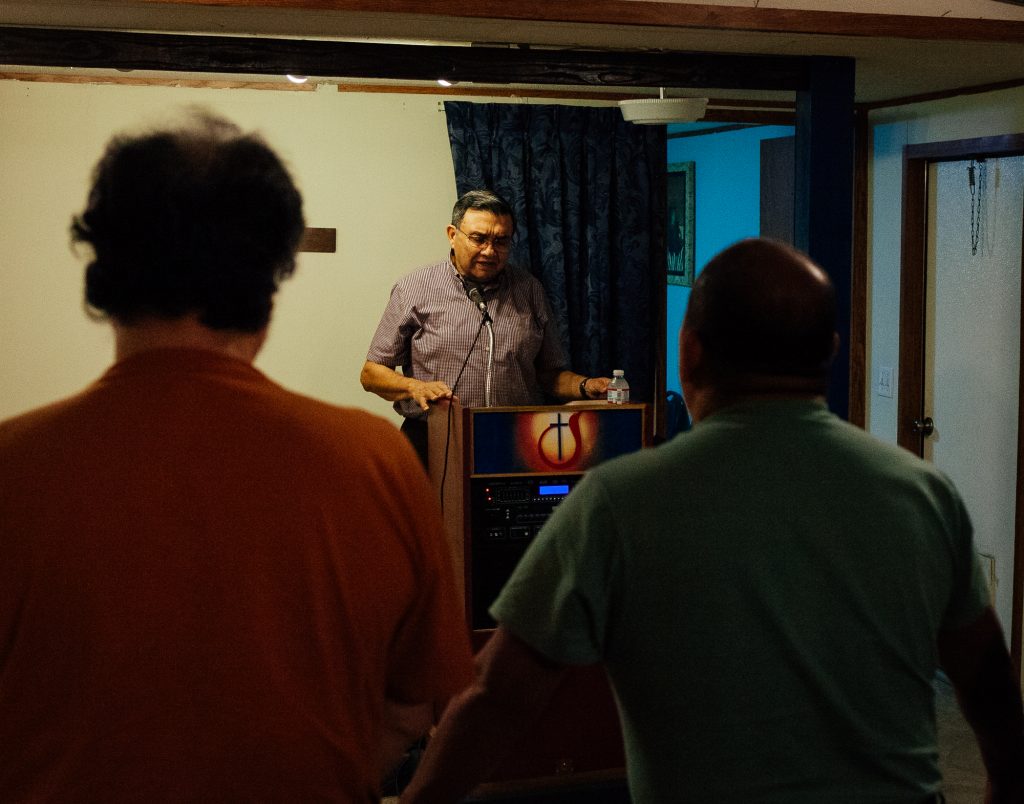

After his first wife passed away, he ended up falling in love with a woman from outside the Catholic faith. She would go to the Catholic Church with him, but they also started going to a Baptist Church. This experience began Luis’s search for the right church. He left the Catholic Church and joined the local Church of God. On Sunday’s Luis attends an “American church” with 200 in the mostly white congregation. On Saturday nights, Luis delivers his Spanish language sermon out of a small trailer – his very own church [see the above photo].

“It doesn’t matter that we are very few. For me, what is most important is the mission. They don’t pay me as a pastor, but I accomplish the mission.” (audio below)

Mississippi

Luis points out how in Mississippi, there are different churches for the region’s different racial groups. He wishes Sundays could be less divided.

“I personally believe we have to destroy these walls.”

He likes living in a rural place with a population of less than four-thousand, like Morton. It’s quiet, things are cheap, and there is no violence. Luis is happy Morton elected its first black mayor, Gerald Keeton Sr.

“I don’t see any difference – people are people. I don’t care if you are black, white, yellow, or green – we are friends.”

Luis doesn’t like big cities like Chicago, where his daughters live.

“The north is not as friendly as we are. The environment there is pretty, the lake is fantastic, but all the time I am in Chicago, I’m missing Mississippi.” (audio below)

The Chilean community in Morton is tiny – just Luis, his sister, brother-in-law, and a few other people. He misses the deep friendships he had in Chile that he hasn’t found in Mississippi.

“I am friends with my neighbor – we talk, but all the time we keep limits.”

Lies

Luis is not a fan of the current president and thinks he is a millionaire only concerned about other millionaires.

“In my opinion, Trump is destroying a lot of things in the United States. He is a negative, racist liar. He is the worst leader. I am not satisfied with everything that is happening now. I have problems even in my church because here, the people are saying, ‘oh, Trump is the hero’ because they are ignorant and don’t know what is going on. The people believed all the lies he was telling them.” (audio below)

Luis thinks the situation in America will likely worsen before it improves.

“If I didn’t have my daughters and grandchildren here, I would go back to my country. See you later, Trump! For me, as a Christian, he is not a Christian at all.” (audio below)

Armed Congregants

Luis is especially concerned about the prevalence of guns in the US and the power of the National Rifle Association. Luis prays that the youth will continue to push for change.

“You don’t need a military rifle unless you have in your mind to kill people. We believe we are in the Christian ‘Bible Belt’. What kind of ‘Bible Belt’ is this when people are just arming themselves?”

In the church Luis attends, they now have two armed congregants – one was a police officer, and the other was in the army. These men carry concealed weapons under their jackets for every service. (audio below)

Future

Luis, twice a widower, is now in his 70s.

“I’ve been living alone for the last… I forget…12 years? It’s okay. I accept my reality.” (audio below)

He has been teaching for over a decade and a pastor for almost two decades. Luis believes that being a Christian is a 24/7 responsibility, not a few hours a week, and he tries to live that way.

“I’m worried about the future because I don’t see people committed to what Christ teaches us. That’s just a pastor’s opinion.”

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love and passion. If you would like to support its continuation, it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes are edited for clarity and brevity.