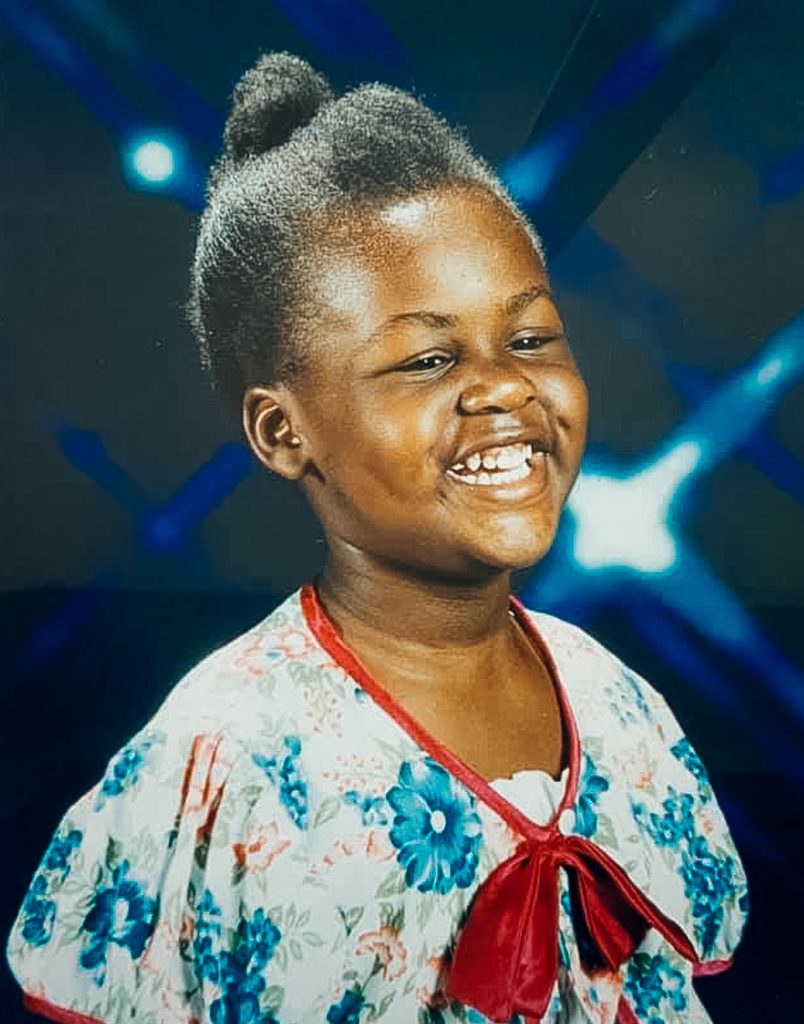

Childhood

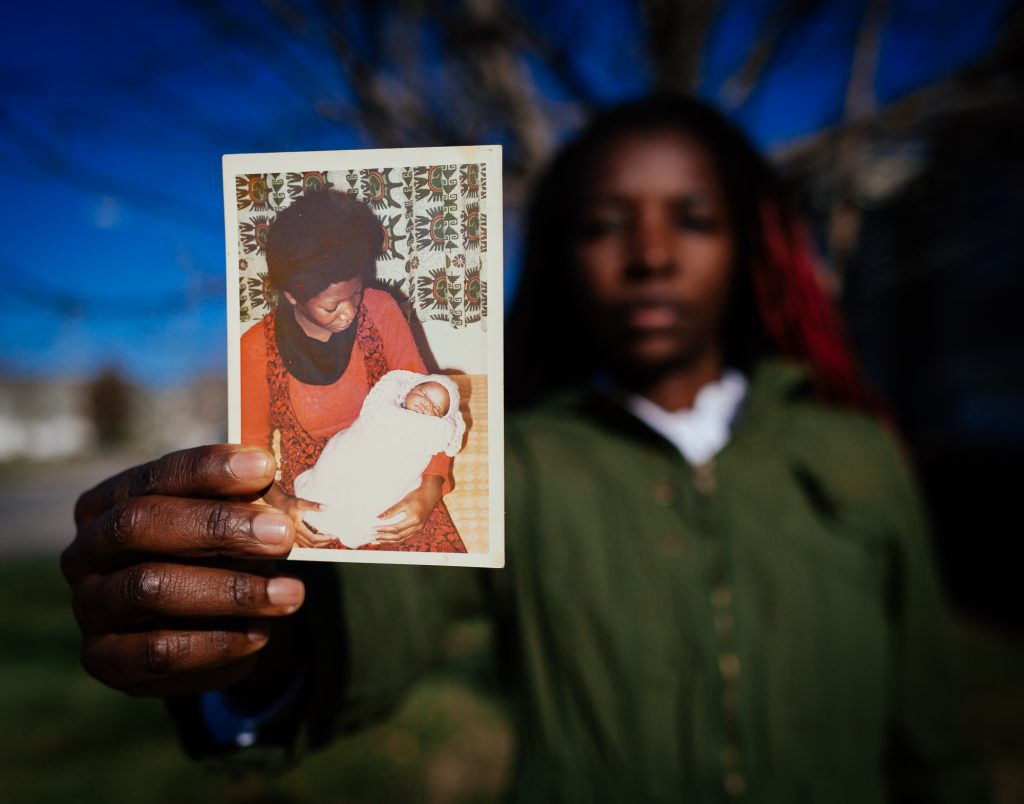

Ben and his six siblings grew up in Kinshasa, the capital city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. His mother stayed home, and his father had a high-profile job, working as the financial advisor to the President of the Senate. Ben witnessed how hard his father worked so his children could have the best of everything from an early age.

“We were going to an expensive school when he could have put us in another school to save money. He did his best for my brother and me to come to the US and have the best opportunity.”

Ben could see how fortunate his family was compared to many other families. Kinshasa is a busy city with many people out in the street finding ways to make some money – cutting hair, carrying things, holding open doors, selling candy.

“There is a lot of joy in my country. Even if the country is in a very bad situation, they try to have fun and enjoy life.”

Ben does not miss Kinshasa’s inefficient public transportation. He explains how it is common to have to fight to get on the bus at rush hour. Ben does miss how social riding the bus can be.

“You would be inside the bus, and then someone would comment on politics, or soccer or music. Everyone on the bus would start talking about that specific topic, and you would all be talking with random people.” (audio below)

United States

Ben didn’t grow up planning to study outside of the DRC, and he definitely didn’t want to go to the US. He had heard too many stories of racism there.

Ben, who grew up speaking French, was attending a private American school in the Congo to learn English, and the school had a presentation about studying in the US that intrigued Ben. His brother already went to Portland Community College in Oregon, and Ben’s dad thought Ben should go to the US too. These events catalyzed Ben’s decision to journey to America.

Ben flew into Portland, Oregon, in 2014 to join his brother and start classes at Portland Community College. He had to make a few adjustments: despite knowing some English from school in the DRC he found it hard to understand Americans, and the food in the US didn’t taste right. He felt like he was only eating it because he was starving. Ben missed dishes like fufu and pondu, which are popular in the DRC.

Ben’s reaction when he couldn’t understand what someone was was to smile back, and assume they were saying something kind. Ben knew racism is a problem in the US, but he wasn’t expecting to encounter it within a week of arriving in the US.

“We were walking to the bus station, and there were two guys, one of them said something to me, so I smiled and walked by. My brother told me he was making a racist comment.” (audio below)

United States

Ben found it stressful being in a new place without family, compounded by the fact that he had no money. Ben’s dad lost his job right after Ben arrived in the US, so he didn’t know how he was going to pay rent, let alone stay in the United States. Luckily friends helped him with rent, and one friend from the student government at PCC helped with tuition. Ben went on to graduate with his associate degree and transferred to Oregon State.

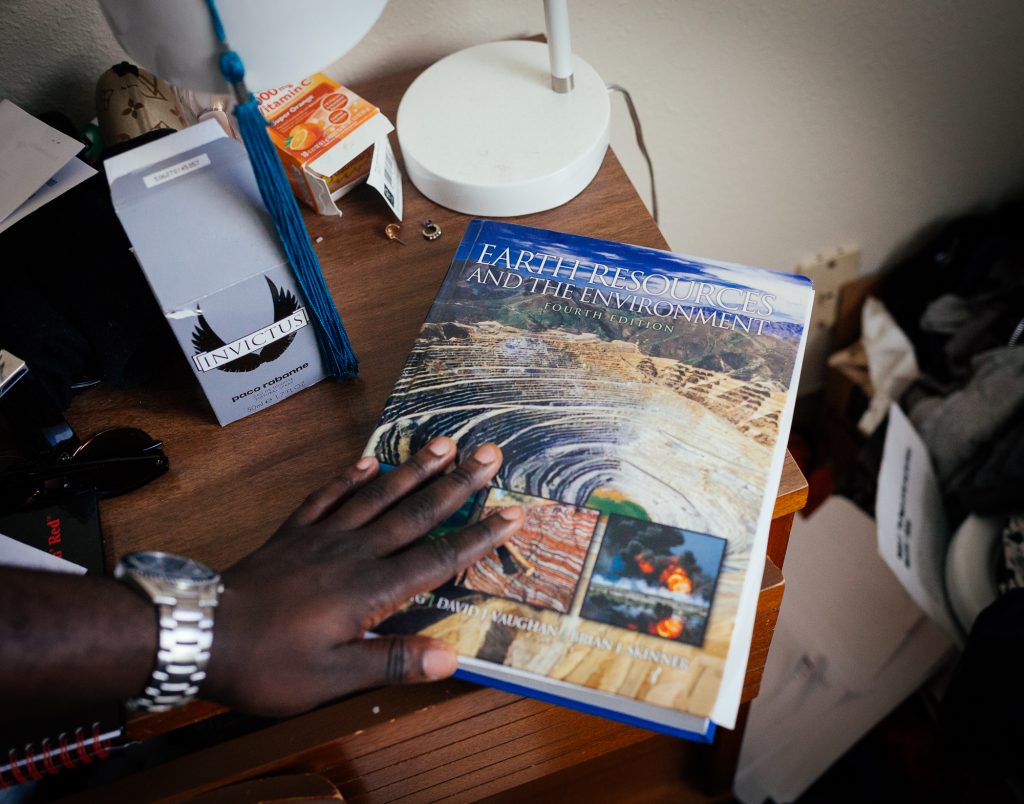

Geology

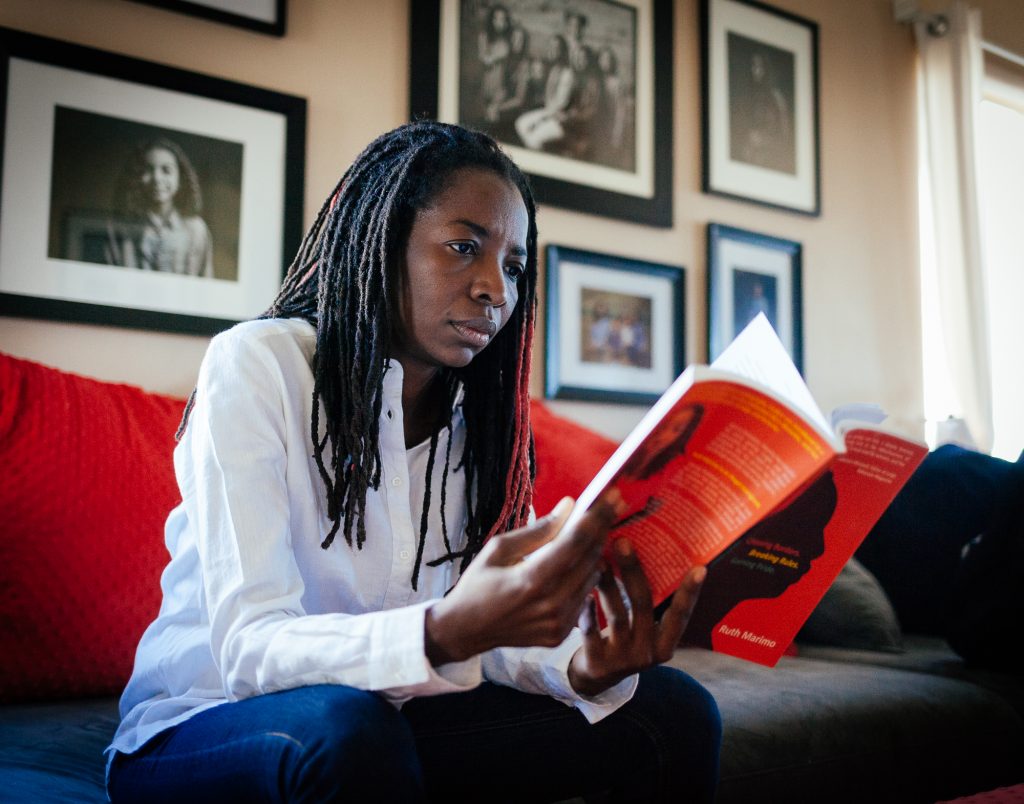

Ben grew up on a continent with a long history of European resource exploitation, as well as human rights abuses of miners, who often are children. Learning about this led Ben to choose geology as his field of study.

“I wanted to study geology so I could eventually go back home and start a mineral company, hire the local population, and give them a good salary.”

Africa

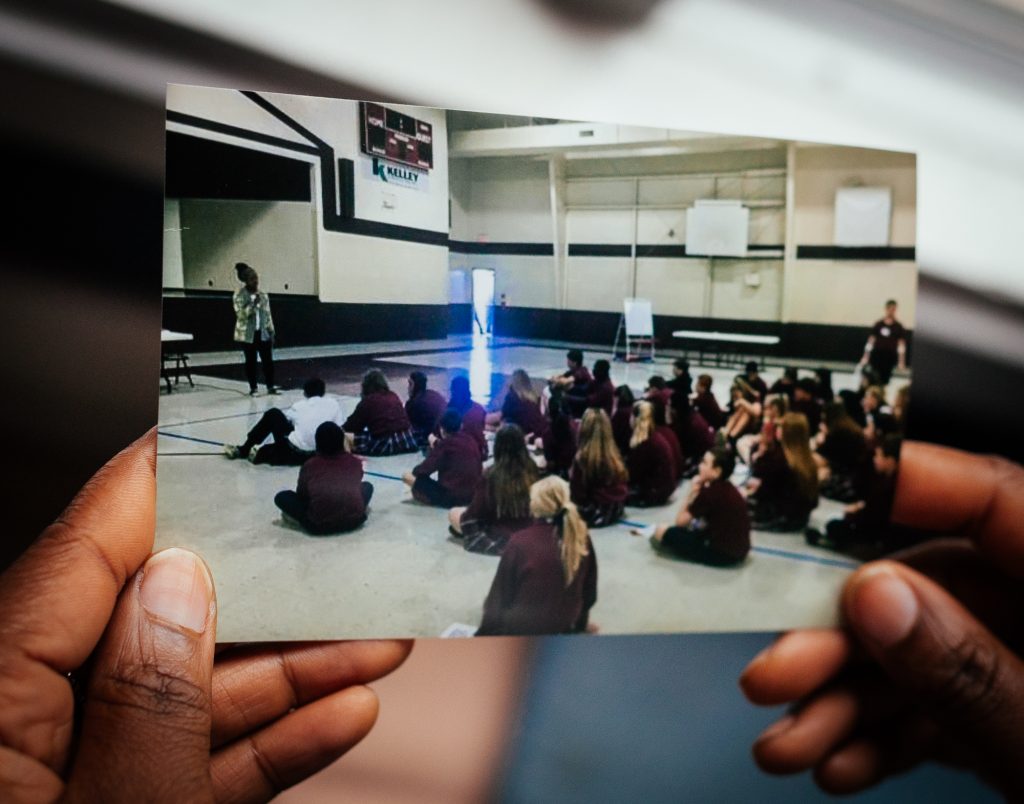

On-campus at Oregon State, Ben tries his best to be a cultural ambassador. He tries to be an advocate for “everything that is African culture.”

“The problem with a lot of immigrants is that we want to be part of this community so badly, and we think that by rejecting our origins or who we are, it will help us be accepted. I don’t think this is the case. Once you reject your origin or your culture so that you don’t have a unique identity, it is harder for people to accept you.” (audio below)

Most people Ben encounters on campus know nothing about the Congo, and very little about Africa.

“They assume it is in Africa because I’m black and my necklace. A lot of the time, people talk about Africa as though it was a country, not a continent. People will ask, ‘what is it like to live in Africa?’ I don’t know because I’ve only lived in my country!” (audio below)

Black On Campus

It isn’t always comfortable being black on Oregon State’s campus. Ben’s community in Corvallis comes mostly from the Black Student Union (BSU) – a place for connecting with others who are going through similar experiences. The BSU is a space where a lot of students can make connections and build community. There is a lot of conversation, listening to music and laughter.

“You have something happen to you, and you think you are the only one. Then you get there, and you see it has happened to other people too.”

They have had hate crimes on campus, and in his time at Oregon State, Ben has heard a lot of racist jokes.

“Oregon State is very white. You could find yourself in a room of 200 people and only two black people in the room. If a teacher starts a conversation about slavery or black people, you will have everyone look at you like you are an expert.” (audio below)

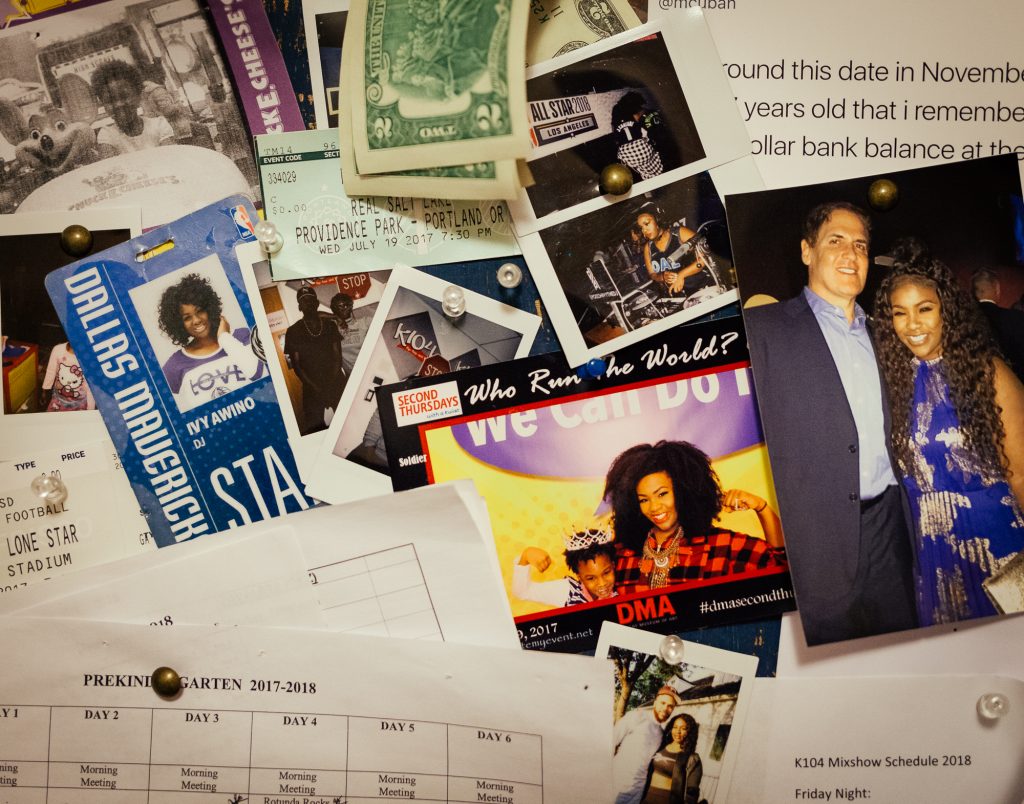

Involved

Aside from the BSU, Ben is also a member of the African Student Association and the “Here to Stay Club” at OSU. He made several friends who are DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) recipients since coming to the US. Ben could feel his friends’ fear after the 2016 election and decided to be a more vocal ally.

The “Here to Stay Club” at Oregon State is working to create a Dreamers Center on campus, something Ben advocated for when he ran for student body president and finished runner-up.

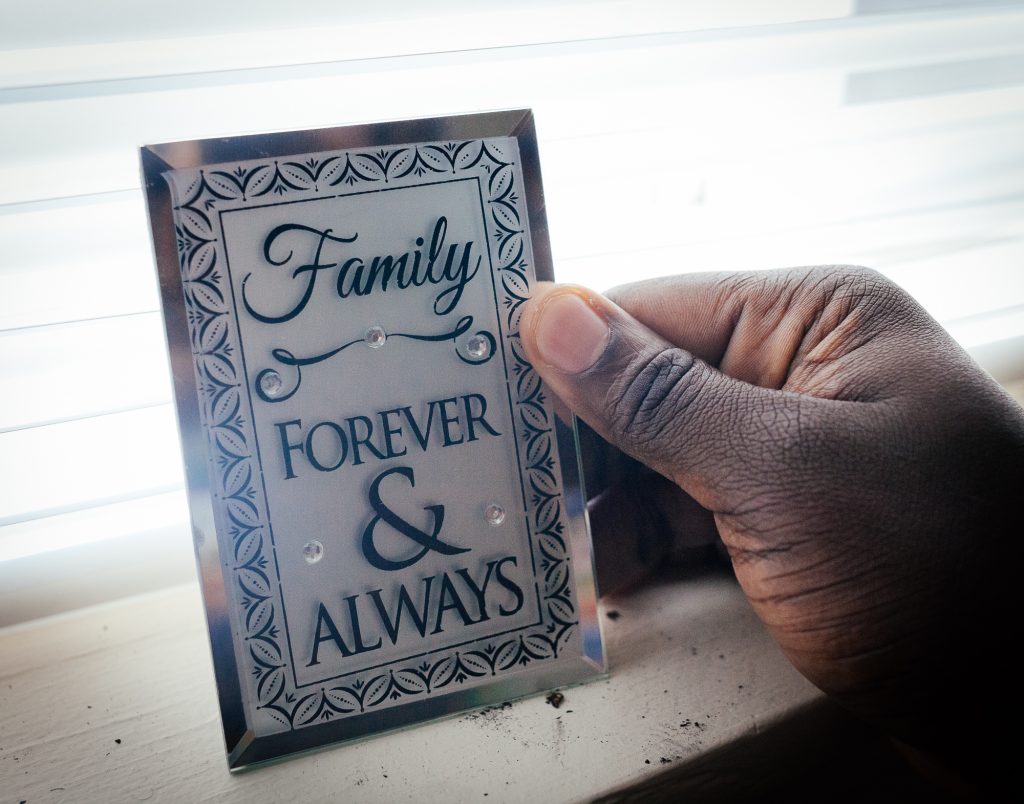

Home

Despite some of the challenges Ben has faced, he considers Corvallis a beautiful place to study. It’s quiet, so he feels like it’s easier to focus on studying.

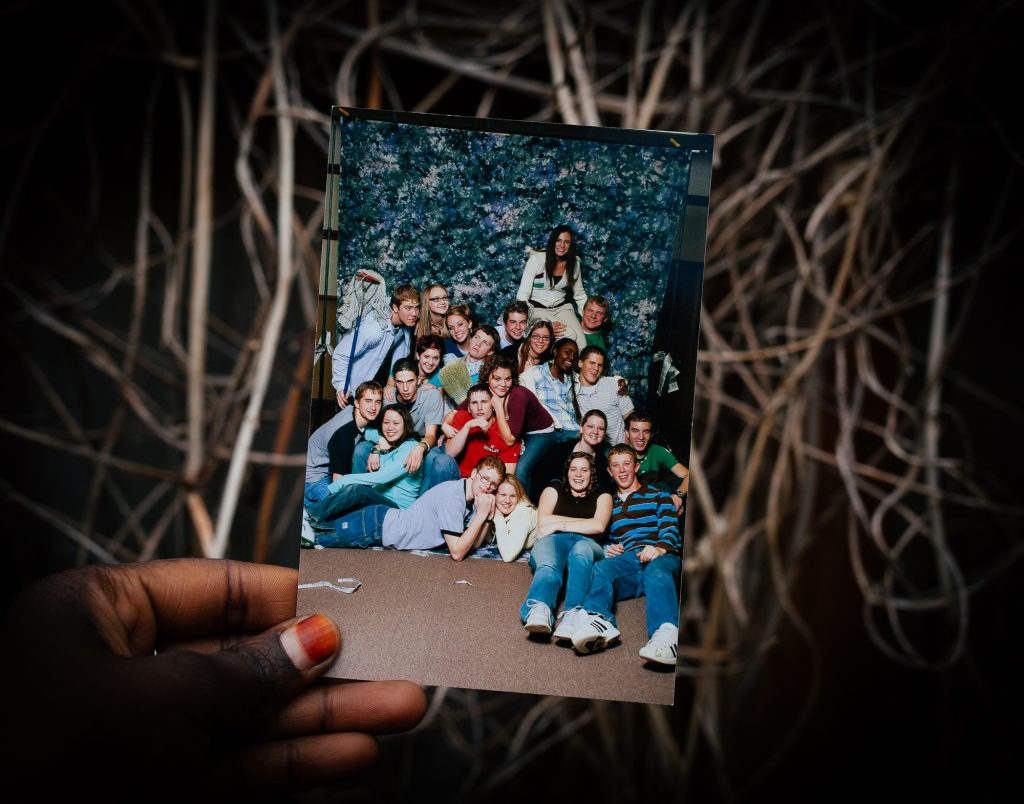

On his first day at OSU, he met his roommate Sierra from New Jersey [see the top right photo]. When Ben had to have surgery on his knee, she was the one who drove him to the hospital and cared for him afterward. She has also helped him when he hasn’t been able to pay the rent. Ben’s life in the US wouldn’t be the same without friends like Sierra.

The Election

The night of the 2016 presidential election, Ben was at a PCC viewing party with the rest of the student council. He was the last student to leave campus that day, and he called a taxi to go home. It was the first time Ben had felt unsafe in an Uber or Lyft. The driver asked Ben,

“Did you watch the results?’ What are you going to do about it? Trump is President now. Are you going to leave or stay?’” (audio below)

Ben thinks America needed the 2016 election to mobilize people into helping marginalized communities.

“If it weren’t for that election, some people would still be at home not doing anything. It brought people together.”

International Student

Ben’s adjustment to being in the US has taken its toll on his mental health. He guesses that many international students share in this experience – especially those who come from countries where mental health is considered taboo. What Ben expected and what the reality was when he arrived in the US was completely different. For instance, the cost of living and the level of pressure at school both surprised him. All of this, plus the challenges he knew his parents were facing back home – like his Dad losing his job – made it much worse.

Since he arrived at OSU, Ben has been trying to talk to a counselor, but there is always a long waiting list.

“When you are mentally not in the right place, how can they expect you to do well in your classes?” (audio below)

Future

Ben’s plan is to finish his bachelor’s degree, get a master’s degree, and then work in the US for a while. After that, he would like to return to the DRC. Ben had two dreams growing up. His first was becoming a soccer star, and that ended with a knee injury. His second dream was to one day become president. He still holds on to that second dream.

As they say in the DRC,

“If you go first, it doesn’t mean you will arrive first.” (audio below)

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love and passion. If you would like to support its continuation, it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes are edited for clarity and brevity.